Technicolor Revolution

Color transforms cinema

The introduction of Technicolor in the 1930s revolutionized cinema, transforming black and white shadows into vibrant spectacles that forever changed how audiences experienced motion pictures.

The journey of Technicolor began with Herbert Kalmus's three-strip process in 1932, but it was Walt Disney's "Flowers and Trees" (1932) that first showcased its true potential. The watershed moment came with "Becky Sharp" (1935), the first feature-length film shot entirely in three-strip Technicolor. Director Rouben Mamoulian and cinematographer Ray Rennahan deliberately composed each frame to exploit the new technology's capabilities, using color as a narrative device. The film's ballroom sequence, with its careful orchestration of reds, blues, and yellows, demonstrated how color could enhance storytelling beyond mere spectacle.

"Gone with the Wind" (1939) marked Technicolor's ascension to Hollywood supremacy. Cinematographer Ernest Haller worked with production designer William Cameron Menzies to create a color palette that evolved with the narrative - from the warm, pastoral tones of Tara's peaceful beginnings to the blazing oranges of Atlanta's burning. The film's success prompted studios to invest heavily in color productions, though the expensive and cumbersome three-strip cameras required specialized technicians and intense lighting setups. This technical complexity led to a distinctive look: deeply saturated colors with a slightly heightened reality that became Technicolor's signature.

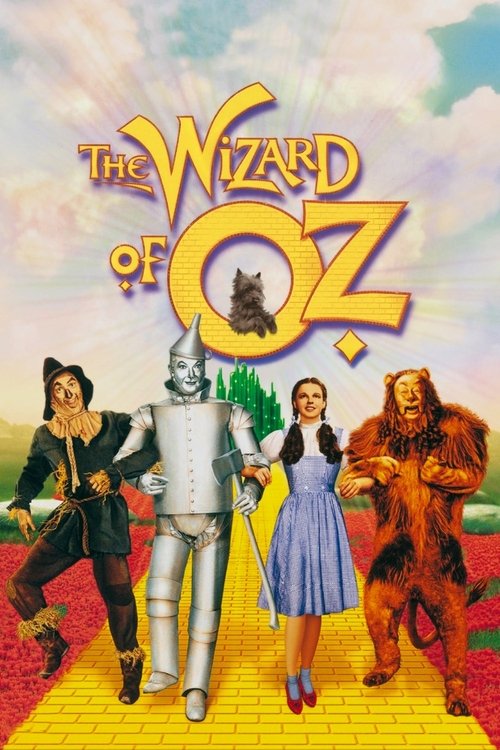

"The Wizard of Oz" (1939) represents perhaps the most iconic use of Technicolor as a storytelling tool. The transition from sepia-toned Kansas to the technicolor Land of Oz created a magical moment that still captivates audiences. Director Victor Fleming and cinematographer Harold Rosson worked with art director Cedric Gibbons to create distinct color zones for different parts of Oz, using color psychology to enhance the narrative. The yellow brick road, the Emerald City's green hues, and the ruby slippers (changed from the book's silver shoes specifically to showcase Technicolor) became central characters in their own right.

The 1940s saw Technicolor reach new heights of sophistication. Powell and Pressburger's "The Red Shoes" (1948) pushed the technology's capabilities to their limit, with cinematographer Jack Cardiff creating hallucinatory ballet sequences that merged color, movement, and emotion. Cardiff's work demonstrated how Technicolor could transcend realism to express psychological states and inner visions. The film's influence extended beyond cinema, inspiring fashion designers and artists with its bold use of color as an expressive medium.

By the 1950s, Technicolor had evolved beyond mere spectacle to become a sophisticated storytelling tool. John Huston's "Moulin Rouge" (1952) recreated Toulouse-Lautrec's artwork through careful color manipulation, while Alfred Hitchcock's "Vertigo" (1958) used color symbolically to enhance its psychological narrative. Cinematographer Robert Burks worked with Hitchcock to create a color scheme where greens represented mystery and attraction, while reds signified danger and obsession. This period marked Technicolor's maturation from a technical innovation to an essential element of cinematic language.

The influence of Technicolor extended beyond Hollywood. British films like "The Tales of Hoffmann" (1951) and "Black Narcissus" (1947) demonstrated how color could create atmospheric and psychological effects. Japanese director Akira Kurosawa's "Ran" (1985), though shot decades later, was directly influenced by Technicolor aesthetics in its bold use of primary colors to distinguish armies and emphasize emotional states. The technology's impact on global cinema created a new visual language that transcended cultural boundaries.

More Ideas

An American in Paris

(1951)

Musical showcasing Technicolor's ability to capture dance

Streaming on TCM

The River

(1951)

Jean Renoir's masterful use of Technicolor in India

Streaming on Criterion Channel

Singin' in the Rain

(1952)

Perfect marriage of color and musical performance

Streaming on HBO Max

All That Heaven Allows

(1955)

Douglas Sirk's emotional use of color symbolism

Streaming on Criterion Channel

More from The Magic of Moviemaking

Hitchcock's Camera Psychology

Visual manipulation master

Birth of Cinema: Méliès to Griffith

Magic and narrative emerge

Studio System & Star Power

Hollywood's golden age machine

Digital Revolution Begins

CGI changes everything

Virtual Production Revolution

LED walls and real-time rendering

AI & the Future of Filmmaking

Artificial intelligence enters cinema

Murnau's Camera Movement Revolution

Unchaining the camera