British Comedy: Ealing to Python

Dry wit and social satire

From the genteel satire of Ealing Studios to the anarchic surrealism of Monty Python, British comedy has wielded wit as a weapon of social commentary and cultural revolution.

The golden age of Ealing Studios (1947-1957) established the template for British comedy's distinctive blend of gentle satire and social observation. Under Michael Balcon's leadership, Ealing produced comedies that reflected post-war Britain's class anxieties and changing social landscape. The studio's masterpiece "Kind Hearts and Coronets" (1949) used pitch-black humor to skewer aristocratic pretension, with Alec Guinness's tour-de-force performance playing eight different characters. Director Robert Hamer employed sophisticated visual composition and subtle editing to enhance the film's mordant wit, while Dennis Price's silky narration added layers of ironic distance.

By the early 1960s, British comedy shifted toward "kitchen sink" realism and working-class perspectives. Films like "Billy Liar" (1963) and "A Kind of Loving" (1962) mixed humor with social commentary, while the "Carry On" series began its long run of innuendo-laden farce. Director Tony Richardson's "The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner" (1962) exemplified this new wave, using comedy to explore class consciousness and rebellion. Cinematographer Walter Lassally's documentary-style photography brought gritty authenticity to these stories, while writers like Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall infused scripts with regional dialects and contemporary attitudes.

The early 1960s saw British comedy turn sharply satirical with "Beyond the Fringe" and "That Was The Week That Was" influencing a new generation of filmmakers. Richard Lester's "A Hard Day's Night" (1964) revolutionized comedy filmmaking with its quick-cut style and documentary techniques. The film's influence extended beyond its Beatles showcase, establishing a new visual grammar for comedy. Meanwhile, "Dr. Strangelove" (1964), though American-produced, represented the apex of British satirical sensibility through Peter Sellers' multiple performances and Stanley Kubrick's mordant direction.

Monty Python's transition from television to film marked a seismic shift in comedy. "Monty Python and the Holy Grail" (1975) combined medieval satire with absurdist humor, while "Life of Brian" (1979) daringly tackled religious themes with unprecedented irreverence. Directors Terry Jones and Terry Gilliam developed a distinctive visual style that matched the group's surreal comedy. Their innovative use of animation, fourth-wall breaking, and non-linear narrative influenced generations of comedic filmmakers. The Python team's intellectual approach to comedy, mixing high culture references with low comedy, created a new paradigm for sophisticated humor.

George Harrison's Handmade Films produced some of the most distinctive British comedies of the 1980s. "Withnail and I" (1987) captured the end of the 1960s dream with dark humor and literary flair, while "A Private Function" (1984) returned to Ealing-style social satire in its story of post-war rationing. Director Bruce Robinson's work on "Withnail" created a new template for cult comedy, combining quotable dialogue with genuine pathos. Cinematographer Peter Hannan's atmospheric photography elevated these films beyond mere comedy into genuine cultural documents.

The 1990s saw Working Title Films establish a new brand of British comedy with international appeal. "Four Weddings and a Funeral" (1994) created the template for the modern British romantic comedy, while "Bean" (1997) successfully translated television comedy to the global screen. Richard Curtis emerged as a dominant voice, crafting films that balanced specifically British humor with universal themes. These films often employed a more polished, commercial visual style than their predecessors, shot by cinematographers like Michael Coulter who brought a glossy sheen to British comedy.

More Ideas

The Man in the White Suit

(1951)

Ealing sci-fi comedy about industrial progress

Streaming on BritBox

Local Hero

(1983)

Gentle Scottish comedy about American businessman

Streaming on Criterion Channel

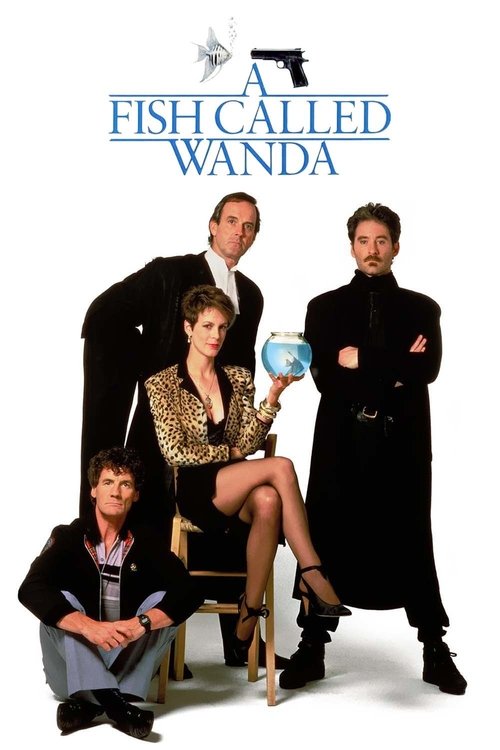

A Fish Called Wanda

(1988)

Anglo-American heist comedy

Streaming on Amazon Prime

Shaun of the Dead

(2004)

Zombie comedy that reinvented British humor

Streaming on Netflix