Silent Comedy Stars

Chaplin, Keaton, and visual humor

The silent era of cinema produced comedy's most influential visual storytellers, with Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd crafting timeless physical comedy through revolutionary cinematography and precise choreography.

The foundation of silent comedy emerged from vaudeville traditions, but quickly evolved into a sophisticated visual language under pioneers like Charlie Chaplin. His Little Tramp character, introduced in 1914's "Kid Auto Races at Venice," became cinema's first global icon through a masterful blend of pathos and slapstick. Chaplin's 1925 masterpiece "The Gold Rush" exemplifies how he elevated physical comedy into high art, with iconic sequences like the bread roll dance and the boiled shoe dinner demonstrating his genius for transforming mundane objects into vehicles for both humor and social commentary. His meticulous attention to visual detail and timing influenced generations of filmmakers.

Featured Films

Buster Keaton's deadpan expression and death-defying stunts created a distinct comedic style that emphasized technical innovation and architectural precision. His 1926 film "The General" represents the pinnacle of silent comedy filmmaking, with elaborate action sequences performed without camera tricks or doubles. Keaton's understanding of cinematography and framing was revolutionary - he insisted on wide shots to prove his stunts were real and utilized the entire frame for visual gags. His work in "Steamboat Bill Jr." (1928) includes the famous house-falling sequence, where Keaton's exact positioning allowed him to survive a two-ton facade falling around him.

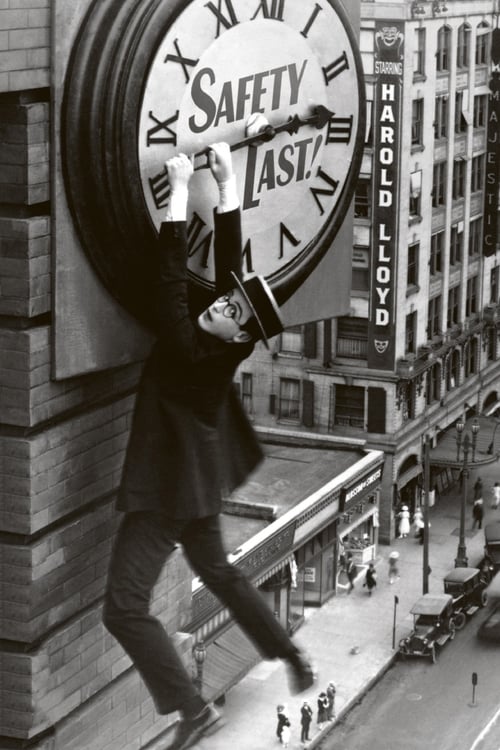

Silent comedians developed sophisticated visual techniques that remain influential today. Harold Lloyd's "Safety Last!" (1923) pioneered forced perspective shots and carefully constructed illusions to create its famous clock-hanging sequence. These innovators understood that comedy required precise framing and timing - Chaplin would often shoot scenes hundreds of times to perfect the visual rhythm. The physical comedy was meticulously choreographed, with Keaton's background in vaudeville informing his understanding of how to stage elaborate gags for maximum impact. Their work established fundamental principles of visual comedy that influenced everything from Jacques Tati to Jackie Chan.

The social commentary embedded in silent comedy often addressed class struggle and modernization. Chaplin's "Modern Times" (1936) brilliantly satirized industrial automation and economic inequality through purely visual means. The famous assembly line sequence, where the Little Tramp is literally consumed by machinery, remains a powerful critique of dehumanizing labor conditions. Similarly, Keaton's "The Navigator" (1924) explored themes of class privilege and self-reliance through the story of wealthy passengers forced to fend for themselves on an abandoned ship.

The influence of silent comedy pioneers extends far beyond their era. Their understanding of visual storytelling and physical comedy directly influenced international filmmakers like Jacques Tati, whose "Playtime" (1967) built upon their traditions of architectural comedy and social observation. Contemporary action-comedy stars like Jackie Chan have explicitly credited Keaton's work as inspiration for their approach to stunts and physical comedy. The precision timing and visual clarity these pioneers developed remain essential studies for modern comedy directors.

More Ideas

Our Hospitality

(1923)

Keaton's historical comedy featuring revolutionary stunt work

Streaming on TCM

The Circus

(1928)

Chaplin's brilliant meditation on entertainment and performance

Streaming on Criterion Channel

The Freshman

(1925)

Harold Lloyd's influential college comedy

Streaming on YouTube

Cops

(1922)

Keaton's short film showcasing perfect comic timing

Streaming on Public Domain