Screwball Comedy: Battle of the Sexes

Rapid-fire wit and romance

The screwball comedy, emerging from the constraints of the Hays Code in the 1930s, transformed sexual tension into verbal sparring matches that defined a uniquely American art form.

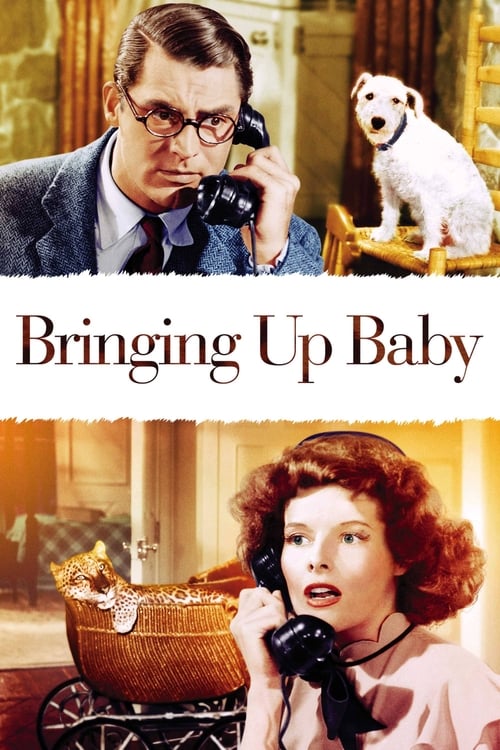

The genre crystallized during the Great Depression, when audiences craved sophisticated escape and studios navigated strict moral guidelines. Howard Hawks' "Bringing Up Baby" (1938) exemplifies the core elements: rapid-fire dialogue, physical comedy, and class conflict wrapped in romantic tension. Katharine Hepburn's wealthy socialite and Cary Grant's stuffy paleontologist establish the archetypal pattern of an unconventional woman upending a rigid man's life. The film's precise timing and overlapping dialogue created a template for verbal comedy that influenced generations of filmmakers. Hawks' direction emphasized physical movement and spatial relationships, using deep focus photography to capture both broad slapstick and subtle facial reactions.

The screwball formula often inverted traditional gender roles, with women driving the action and men responding to their chaos. Frank Capra's "It Happened One Night" (1934) established this dynamic with Claudette Colbert's runaway heiress commanding equal footing with Clark Gable's cynical reporter. The film's success - sweeping the major Academy Awards - legitimized comedy as serious filmmaking. The famous "Walls of Jericho" blanket scene demonstrated how filmmakers could suggest sexuality while maintaining Production Code compliance. The film's road trip structure became a template, allowing characters to move through different social classes while maintaining the intimate focus on their developing relationship.

Preston Sturges elevated the genre's satirical elements while maintaining its romantic foundations. "The Lady Eve" (1941) weaponizes Barbara Stanwyck's sexuality against Henry Fonda's naive snake researcher, creating complex power dynamics that subvert audience expectations. Sturges' background as a playwright shows in his intricate dialogue construction, with conversations that layer meaning and innuendo. His camera work often holds on reactions rather than actions, allowing audiences to track the emotional evolution of characters through subtle performance changes.

George Cukor's "The Philadelphia Story" (1940) represents the genre's peak of sophistication, using its triangular romance to explore class, privilege, and personal growth. Katharine Hepburn's Tracy Lord embodies the screwball heroine's complexity - intelligent, difficult, and ultimately human. The film's structure allows each character to reveal deeper layers beneath their archetypal surfaces. Cukor's elegant direction emphasizes the architectural grandeur of the setting while maintaining intimate focus on character interactions, creating a perfect balance between social commentary and romantic comedy.

Technical innovations drove the genre's development. Directors like Mitchell Leisen ("Midnight," 1939) perfected the art of staging complex physical comedy within sophisticated settings. Cinematographers like Joseph Walker, who shot many of Capra's films, developed techniques for capturing both verbal wit and physical comedy in the same frame. The genre demanded precise timing and camera movement to maintain both narrative momentum and visual clarity. These technical achievements influenced filmmaking well beyond comedy, particularly in how dialogue scenes could maintain visual interest through careful blocking and camera placement.

The social impact of screwball comedies extended beyond entertainment. These films presented working women as equals, showed class mobility as possible (if complicated), and suggested that marriage should be based on mutual respect and shared humor rather than social obligation. "His Girl Friday" (1940) features Rosalind Russell as a journalist equal to or superior to her male colleagues, while "Theodora Goes Wild" (1936) champions female sexual and creative freedom against small-town morality.

More Ideas

Nothing Sacred

(1937)

A reporter exploits a woman he believes is dying, leading to romantic complications

Streaming on TCM

Twentieth Century

(1934)

A Broadway director tries to win back his former star on a cross-country train journey

Streaming on Criterion Channel

Ball of Fire

(1941)

A group of professors writing an encyclopedia encounter a nightclub singer hiding from gangsters

Streaming on TCM